For generations, the primary school mathematics classroom has been a familiar scene: rows of pupils bent over textbooks, working through columns of abstract sums. The pedagogical model was straightforward: the teacher demonstrated a procedure on the chalkboard, and pupils practiced it repetitively on worksheets. While this method could produce procedural fluency for some, it often failed to cultivate genuine mathematical understanding or a lasting love for the subject. For many, maths became a source of anxiety, a rigid set of rules to be memorized rather than a dynamic language for exploring the world. The transition from this traditional model towards one centred on interactive, narrative-driven learning represents not merely a change in tools, but a fundamental shift in our philosophy of what it means to be “good at maths.”

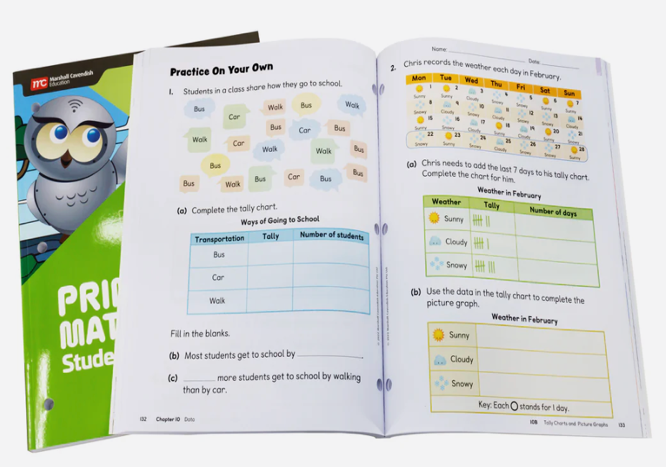

The limitations of the textbook-centric approach are well-documented. Textbooks often present mathematics as a closed system of isolated skills. Problems are decontextualized; the notorious “Two trains leave different stations 100 kilometers apart. If one train travels 40 km/h and the other travels 60 km/h, how long will it take for them to meet?” problem is a classic example of a scenario devoid of real meaning for a young child. This abstraction can create a significant barrier to engagement. Pupils struggle to answer the question, “Why do I need to know this?” when the subject is presented as a series of disconnected exercises. Furthermore, the one-size-fits-all nature of a textbook fails to accommodate the diverse range of learning paces and styles within a single classroom. The focus on a single, correct answer and the fastest computational method can stigmatize mistakes, discouraging the very experimentation and productive struggle that is essential for deep conceptual learning.

The initial integration of technology into maths education often simply digitized these old practices. Early educational software frequently amounted to “digital worksheets” or “drill-and-kill” games, where students answered multiple-choice questions to receive a reward. While this added a layer of novelty, it did little to address the core issues of disengagement and lack of conceptual depth. The real transformation began when educators and developers started leveraging technology not for replication, but for reimagination. The goal shifted from using technology to deliver instruction, to using it to create immersive learning environments where students could actively construct their own understanding.

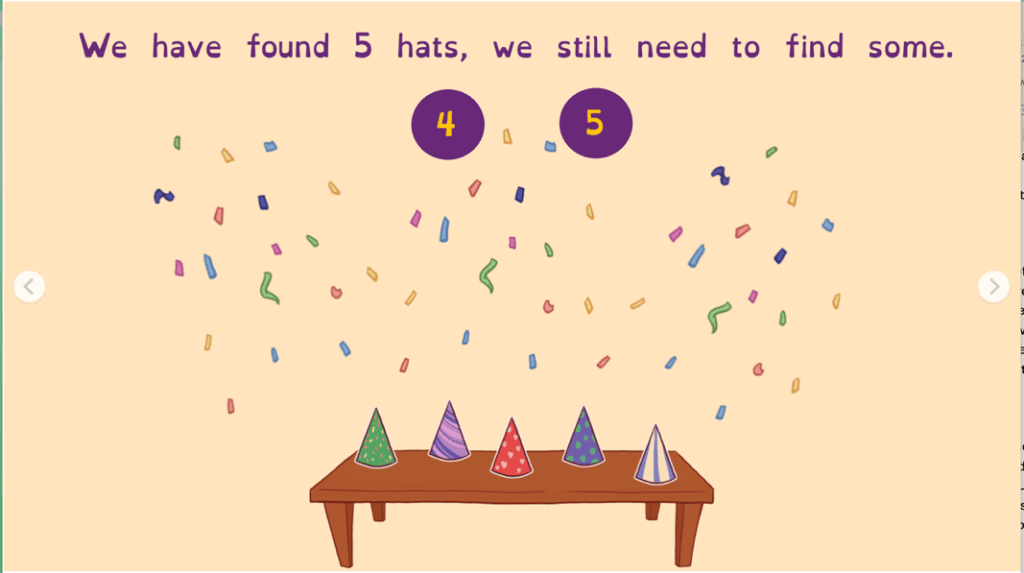

This is where the power of the interactive story emerges. Humans are inherently wired for narrative; we use stories to make sense of the world, to remember information, and to empathize with others. By embedding mathematical concepts within a compelling storyline, we provide the context that textbooks lack. Suddenly, division isn’t just a procedure; it’s the act of sharing treasure fairly among a crew of pirates. Geometry isn’t about memorizing shapes; it about designing a fortress strong enough to withstand a dragon’s attack. The mathematics becomes purposeful. It is a tool the character needs to overcome a challenge and progress in their journey. This narrative framework answers the “why” question powerfully and intuitively: you need to learn this to help the hero save the day. A very good example are the interactive online books created as part of the Erasmus+ ABIBooks project. (https://abibooks-project.eu/ro/)

The benefits of this narrative-driven, interactive approach are multifaceted. Firstly, engagement soars. A child invested in a character’s fate is motivated to solve the mathematical puzzles that stand in their way. The learning becomes intrinsic, driven by curiosity and a desire to see what happens next, rather than by the extrinsic motivation of a grade or sticker. Secondly, interactive stories naturally promote conceptual understanding. In a game like “Prodigy Math”(https://www.prodigygame.com) or “DragonBox,” (https://dragonbox.com/) pupils don’t just learn that `a x b = c`; they manipulate visual blocks and see the multiplicative relationship unfold. They develop a “feel” for fractions by slicing up a virtual cake or dividing a magical potion. This visual and tactile exploration builds a robust mental model that is far more resilient than a memorized rule.

Moreover, this environment reframes the role of failure. In a traditional setting, a wrong answer is often met with a red ‘X’. In an interactive story, a failed solution is simply a puzzle to be rethought. The pupils can try again immediately, testing a new hypothesis without fear of judgment. This fosters a growth mindset, where challenge is embraced and mistakes are seen as valuable steps in the learning process. The narrative context provides a safe space for productive struggle, allowing students to develop resilience and problem-solving stamina. This is also the aim of the Erasmus+ Enigmathico project, which involves creating interactive themed stories with mathematical puzzles that, once solved, will gradually lead to the unfolding of the action, the narrative conflict, and the dénouement of the story. In the project, pupils engage with story-based mathematical challenges connected to real-life issues such as the environment, sustainability, or everyday problem-solving. This would make the connection to the project clearer and highlight the balance between imaginative and realistic scenarios.

Crucially, the teacher’s role evolves from being the “sage on the stage” to becoming a “guide on the side.” Freed from the sole responsibility of direct instruction, the educator can use the interactive story as a rich diagnostic tool. As pupils play, the software can provide the teacher with real-time data on individual struggles and breakthroughs. The teacher can then facilitate small-group sessions to address common misconceptions, pose deeper questions to extend learning, and provide targeted support where it is needed most. The classroom becomes a dynamic workshop of mathematical inquiry, rather than a passive lecture hall.

Of course, this transition is not about discarding all traditional resources. A well-crafted textbook problem still has its place for building procedural fluency. The future of primary maths education is not a binary choice between old and new, but a thoughtful blend. It is a hybrid model where interactive stories provide the engaging, conceptual foundation, and teachers use a variety of tools (including targeted practice) to build upon that foundation.

The conclusion is clear: when we wrap math in a story, we give it a soul. We transform it from a subject to be memorized into an adventure to be lived. And in doing so, we are not just teaching students how to calculate; we are inspiring a new generation to see the story hidden within the numbers all around them.

References

1. Chehak Arneja and Dr. Sneha Tyagi, The importance of using stories for teaching-learning of mathematical concepts , in

https://www.allstudyjournal.com/article/445/2-4-109-686.pdf

2. István Czeglédy, András Kovács ,How to choose a textbook on mathematics? in

https://dppd.ubbcluj.ro/adn/article_1_2_2.pdf

3. Kirstin Mulholland, Using storybooks to promote high-quality talk in maths, in

https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/early-years/storybooks-maths